The Five Best Films of the 2023 Toronto International Film Festival

Stephen David Miller runs down the best of the fest.

[DChen’s Note: Today I’m pleased to present a dispatch from a longtime listener/supporter who recently attended the Toronto International Film Festival. Stephen David Miller is a writer and co-host of The Spoiler Warning podcast. In the piece below, Miller runs down the five films from the festival that he found most notable (and that you’ll probably be hearing a lot about in the months to come). Please note that this piece will describe the premise of the movies that are named, but will avoid spoilers. If you enjoy the piece, be sure to check out Stephen’s podcast!]

Every festival has its own, unique character. Sundance is for documentaries and newly-minted indie darlings; SXSW is for the underdogs, heartwarming sleeper hits; Cannes is for arthouse and international fare. And though Venice and Telluride typically get the first bite of the apple in late August/early September, the following week at Toronto is where certain narratives really take shape. Buzzy star-studded vehicles announce their march to the Oscars, while earlier festival darlings get a chance at greater scrutiny by a general audience. There’s a reason the TIFF People’s Choice Award is considered a major awards season bellwether: This is where the film industry goes to pressure test its product.

The SAG-AFTRA and WGA strikes loom large over the festival this year, with many actors and creators opting not to attend. Without the built-in PR boost of a glitzy red carpet, a handful of major films skipped the fest entirely; other premieres which might have coasted on the charisma of their superstar casts were instead met with muted receptions. If this delivered a well-deserved financial blow to the studios, it also had the side effect of leveling the playing field. No single film monopolized audience attention, lending a sense of possibility to even the tiniest screening.

Over the past week, I’ve seen strong entries in just about every genre: inspirational biopic (NYAD, One Life), naturalistic drama (Close To You, How To Have Sex), star-driven comedy (Wicked Little Letters, Hit Man), contemplative sci-fi (Fingernails), finely-tuned tearjerker (Monster), charming musical (Flora and Son), and heartwarming coming of age saga (The Holdovers). All are well worth your attention. But the stories that most resonated with me all seemed to be orbiting one, recurring theme: Selective focus, i.e. the filters we apply to transform the world’s chaos into palatable stories, recognizable patterns. What do we tune out, what do we amplify, and what gets lost or revealed in the process? Let’s dive in with my five favorite films of the festival, in no particular order.

American Fiction (dir. Cord Jefferson)

Author and professor Thelonius “Monk” Ellison (Jeffrey Wright) is tired. He’s tired of censoring literary history to coddle sensitive white students, who somehow seem more scandalized by racism than he is. He’s tired of the Catch-22 imposed on him by the publishing industry, whose superficial appetite for diversity puts his race front and center—a “prominent Black voice,” a reflection of some monolithic “Black experience”—only to then be disappointed when his novels break their mold. He’s tired of the art white audiences would prefer he make instead, and the euphemisms they use to describe it: “authentic” meaning wholly fixated on poverty or trauma; “raw” meaning inartful, simplistic, underbaked; “searing” meaning morally obvious. As he takes stock of the novels by Black authors that do seem to sell, his thoughts drift from contempt to jealousy to cynical inspiration. “Anyone could write this.” “I could write this in my sleep.” “...maybe I will write this, just to prove a point...”

American Fiction is based on the novel Erasure by Percival Everett, published in 2001. Having not yet read it, I’m not clear on how much writer/director Cord Jefferson changed to bring Everett’s story up to date, or if American attitudes around race have simply not progressed in over twenty years. I say this because more than any other film at the festival, this one rings as a damning indictment of our particular moment: a blistering satire about white audiences’ surface-level empathy, performative solidarity, and hunger for art that offers easy absolution. Like Sorry To Bother You (2018), this is the sort of work that demands to be seen in a crowded theater, feeding off of audience discomfort. Brilliantly realized in a career-best performance by Wright, Monk Ellison is witty, perceptive, and jaded. Though he claims to resent readers’ limited appetite for a certain type of story, his resentment often curdles into mockery of the stories themselves. And there’s something very uneasy about the laughter his mockery elicits, particularly in a primarily white audience, like the one at my TIFF screening.

That unease, I suspect, is intentional. While American Fiction has no shortage of cynical takes, it’s also a somber reflection on the limits of that cynicism. That push and pull between bitterness and sincerity—between Monk’s razor-sharp critique and the emotional distance it creates—is the real beating heart of the film. This is best expressed in the character of Sinatra Golden (Issa Rae), the novelist whose success first provokes his contempt. For every joke seemingly made at her expense, there is another challenging Monk and his knee-jerk instinct to dismiss her.

Unlike the “searing” art Monk’s publishers crave, American Fiction is short on obvious moral answers. That open-endedness is what makes it such a surprising (and refreshing!) winner of this year’s People’s Choice Award. But while it doesn’t offer answers, I do believe it has a thesis, one which has something to do with staying open. Staying open, as a consumer, to art that challenges expectations; staying open, as an artist, to cutting criticism; staying open, as a critic, to the limits of your cleverness. Whether your preference is for feel-good inspirational fare or neurotic meta-fiction, don’t cling to it so tightly you lose sight of other stories.

The Royal Hotel (dir. Kitty Green)

Director Kitty Green is also interested in relative volumes and the stories that might otherwise get drowned out. In The Assistant (2019), a film about sexual harassment in a fictionalized Miramax, she toyed with audience expectations by fashioning a monster movie which never shows the monster. But rather than depict the atrocities of the film’s Harvey Weinstein stand-in, she muted the drama to explore the structures that allowed him to exist: nervous conference room chuckles, whispered watercooler insinuations, the dull din of bureaucratic self-preservation. One monster may be vanquished, it hints, but a deeper threat lives on in the conditions that allow monsters to flourish.

With The Royal Hotel, Green continues her exploration of toxic masculinity and the structures that uphold it. But if The Assistant was all about muffled emotions, this time she’s choosing to crank up the volume, amplifying frequencies only one character really seems to hear. Hanna (Julia Garner) and Liv (Jessica Henwick) are a pair of college-aged friends on a backpacking trip through Australia. Short on cash and in search of adventure, they land a temporary gig tending a run-down bar in a mining town deep in the outback. The bar’s patrons are almost exclusively men and, to no one’s surprise, they’re obnoxious. But where Liv shrugs off their behavior as silly boys-will-be-boys antics, Hanna senses something more nefarious in every exchange—the implicit threat that undergirds unwanted flirtations, the venom at the heart of “just a joke.” Liv wants to ignore it, maybe even humor them for tips. Hanna thinks they ought to leave as soon as possible.

What follows is a tense psychological horror about gaslighting – a heart-palpitating race whose runner is continually told to lower her pulse, to smile at the monster rather than escape it. Like last year’s Men, that monster is multifaceted: everyone from the overt creeps to the blandly respectful “nice guys” to the bar’s paternalistic owner (a fantastic Hugo Weaving) is presented to the audience as a possible threat. Some threaten them directly, while others stand aside or even try to help, but all are complicit in a patriarchal system.

If I’m painting this as some heady, torturous exercise, make no mistake: This is also a rip-roaring, crowd-pleasing genre flick. The system may be irreparably broken, but there’s a visceral thrill in watching broken things burn.

Thanks for reading Decoding Everything! Please subscribe and share to support us.

The Zone of Interest (dir. Jonathan Glazer)

In the weeks following Oppenheimer’s summer release, a few questions permeated the discourse. How do you depict an irredeemable tragedy, and is omission an abdication of responsibility? Is it possible to center a film around a character who perpetrated evil without implicitly garnering sympathy? That cold pragmatism, which dilutes even the gravest war crime into a scientific puzzle box or sterile bullet-pointed agenda—how do you show it without in some way excusing it? As I watched that thoughtful conversation devolve into a shouting match, I couldn’t help but wonder what chaos The Zone of Interest will unleash.

Loosely based on Martin Amis’ 2014 novel of the same name, Jonathan Glazer’s latest covers a brief stretch of time in 1943. Its subject, Rudolf Höss, is an operations manager who has relocated to Poland with his family. They fill their days like any upper-middle-class family might. Rudolf (Christian Friedel) spends hours in his office dictating mind-numbing memos, while his wife Hedwig (Sandra Hüller) tends to her massive garden in the back. In the evenings before bed, they compare notes on their respective daily stressors, encouraging one another to relax. They do. Over the weekends they might throw a birthday party, host a visiting relative, or take their children to the river for a picnic and a swim. What we never witness is also the horrific subject of the film, lying just beyond the wall of Hedwig’s garden: the Auschwitz concentration camp, where Rudolf works as commandant.

It’s a chilling concept, executed with pitch-perfect precision. Glazer takes Kitty Green’s trick of selectively muted drama to its logical extreme: a dispassionate remove that totally flattens his subjects, reducing them to cogs in a machine. Shot less like a film than a dry anthropological study—what DP Lukasz Zal likened to “Big Brother in a Nazi house”—the film is intentionally numbing, lulling us into the daily tedium of the Höss family drama only to jolt us with reminders of the nightmare out of frame. The result is profoundly disturbing. In its unflinching exploration of the banality of evil, it most reminded me of the 2012 documentary The Act of Killing—a terrifying look at our ability to compartmentalize and the ways empathy can harden to a callus.

That probably sounds like a relentlessly brutal experience to sit through—and make no mistake, this is very heavy stuff. But seeing it a second time with a more mainstream-skewing audience, I was struck less by Glazer’s ruthlessness than his tiny moments of restraint. Whenever the film’s construct threatens to overwhelm us, he sprinkles in a subtle nod to the potential of hope. There’s a musical sequence in particular which would seem trivial if put in writing, but calibrated to the relative volumes The Zone of Interest is playing in, it’s more moving than any melodrama: a quiet reminder that evil, even the most unimaginable variety, does not hollow out those who suffer the way it does those who ignore it.

How do we stay attuned to the enormity of other people, lending weight to their pain without letting it numb or overwhelm us? I don’t know that an answer exists. But I’m convinced that when we wall ourselves off from the world—tending to our gardens of comfort and convenience, ignoring the horrors at their root—we run the risk of losing some vital, feeling aspect of ourselves. And I suspect that the best hedge against that risk is to absorb the contradiction that we live in, to feel it as unsettling, uncomfortable. No film in recent memory has provoked that discomfort quite like The Zone of Interest. It’s the most stunning artistic achievement of the year by far, and it demands to be reckoned with.

The Boy and the Heron (dir. Hayao Miyazaki)

Much of Hayao Miyazaki’s filmography is, in its own way, an expression of similar tensions: reckoning with a world that is both lovely and cruel, wondrous and tragic. He frequently constructs his own walled off gardens, bespoke universes unlike our own. But he doesn’t use them to escape the brutal realities of life. Instead, they act as tiny prisms to recontextualize those realities, leveraging a fuzzy, dreamlike logic to tease out contradicting feelings.

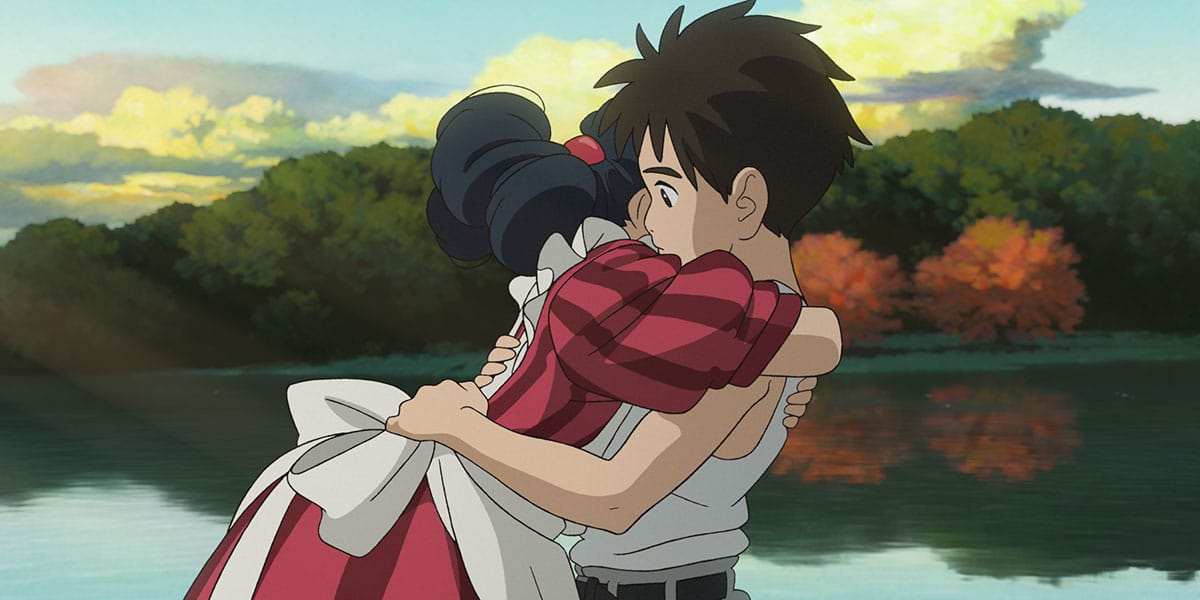

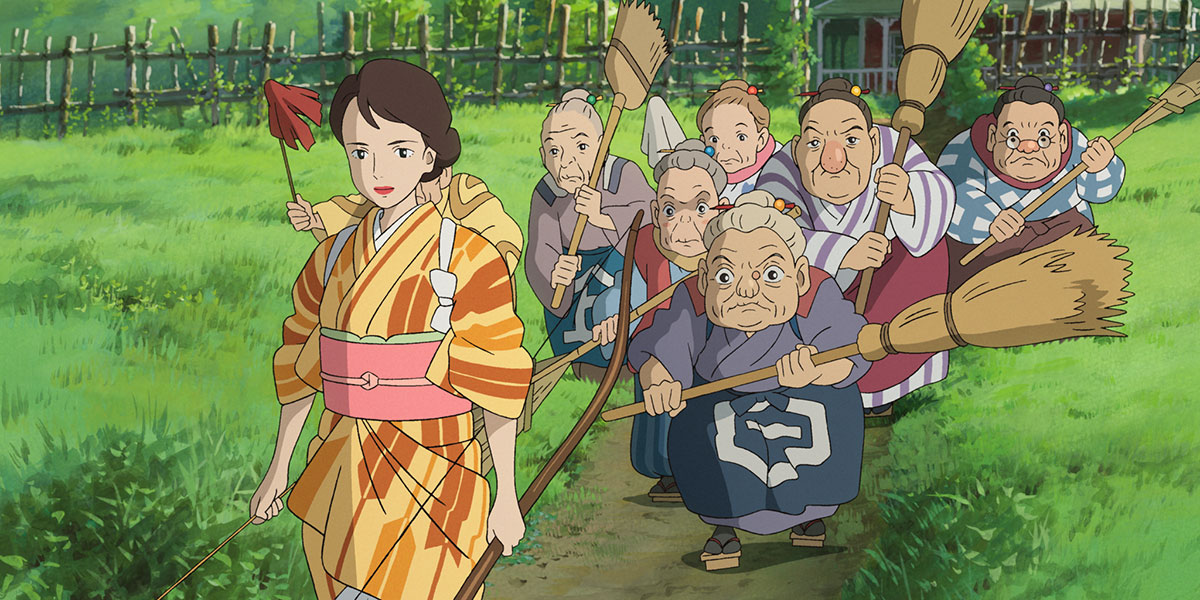

The Boy and the Heron—or, to use its far more apt Japanese title, How Do You Live?—again finds us in a secluded home in 1943. Miyazaki’s swan song centers around 12-year-old Mahito (Soma Santoki), who has just lost his mother in a hospital fire. While it’s a clear (and harrowing) allusion to the Bombing of Tokyo, the film isn’t concerned with historical tragedies so much as the feelings that linger on. Though all adults around him seem intent to move on with their lives, Mahito remains stuck in place. He can’t make sense of a world without his mother, but also can’t bear to be reminded of her absence—haunted by fragmented memories, visions of fire. When a heron appears and dares to speak of her existence, he fashions a bow and arrow to hunt it down.

Like Spirited Away’s Chihiro, Mahito soon finds himself in an alternate world packed with fantastical creatures and fluid, hazy rules. For all its peculiarities, this world is eerily familiar, serving as emotional scratch paper on which Mahito (or Miyazaki) can work through complicated thoughts: unresolved feelings around the death of his mother; the absurdity of war and the seeming impossibility of peace; the lack of perfect heroes or truly nefarious villains; the sense of things always on the verge of toppling over. As with Wes Anderson’s Asteroid City (2023), it operates as both a narrative about grief and a commentary on the artistic process. Why do we tell stories, and does any of it make a difference? Brought to life with intricate, hand-drawn animation, The Boy and the Heron is as gorgeous as anything in the Studio Ghibli catalog. Miyazaki has no real resolution to offer, but even unresolved questions can be lovely.

Perfect Days (dir. Wim Wenders)

There’s more than one way to tease out wonder. If Miyazaki uses fantasy to amplify the world’s subtle beauty, Wim Wenders points a microscope at the beauty that hides in plain sight.

Hirayama (Kōji Yakusho) lives alone in a Tokyo apartment, and his days follow a particular routine. He wakes up before sunrise, waters his plants, and sips vending machine coffee on his drive out to work. A sanitation worker, he spends hours cleaning toilets in the bustling neighborhood of Shibuya. Though he scrubs every inch of them with methodical precision, he knows they’re destined to be dirty the next morning. Exhausted from the scrubbing, he heads to an onsen, has dinner and drinks at a bar, and reads a few pages of a book as he drifts off to sleep. From sunrise to sundown, he rarely utters a word.

On paper, this could easily be played as a raw social drama, showing Hirayama’s slow loss of dignity via numbing routine. But in Wenders’ eyes and, more crucially, in Hirayama’s, his routine is anything but numbing. He chooses instead to be present and attentive to the loveliness (and absurdity) of every minute detail. You notice it in the cassette tapes he listens to on those daily morning drives: be it Nina Simone, Patti Smith, or Lou Reed’s titular “Perfect Day”, he engages with music as if hearing it for the very first time. You find it, too, in his wordless interactions at work as he encounters people at their most vulnerable, and receives them with grace. When they refuse to make eye contact, he chooses not to feel slighted; rather, he smiles at the humor of it, the humanness of their fear. The predictability of his life only makes it easier to stay focused, soaking in the textures that surround him. The way sunlight refracts on the outer walls of his toilet stalls. The precise shape a tree makes when framing the sky, its branches casting shadows as they sway. Do overlapping shadows yield a darker color? They ought to. Meaning tends to deepen with repetition. At night, he’ll revisit these impressions as he drifts off to sleep, mental Polaroids comprising yet another perfect day.

Wim Wenders’ answer to Jim Jarmusch’s Paterson (2016), this is a soulful meditation on the poetry of living. Though of course, not all poetry is happy. As we follow a week in our protagonist’s life, we witness subtle deviations which throw a wrench in his routine. Hints of his history are revealed to us, too; deeper pains, the reasons for his silence. But unlike the silent observer in Wenders’ Paris, Texas (1984), Hirayama isn’t keeping any of his feelings bottled up. He’s simply made a choice to quietly mine all of life for beauty; his sadness is just another texture.

I adored Perfect Days when I first caught it at Cannes, and this week’s second viewing only deepened my affection. Like Hirayama and his daily routine, repetition lent me the opportunity to pay closer attention, to luxuriate in the song between the notes. Even my screening, packed with noisy audience members who would have otherwise annoyed me, felt like a chance to practice that same grace: I smiled at the frustration and let it go. I could watch this film once a year and be made better in the process. Turn up the volume and listen.

Stephen David Miller is a technologist, writer, and podcaster living in the Bay Area.

Other Stuff David Chen Has Made

- Over on Decoding TV, Patrick Klepek and I discussed the Netflix live action adaptation of One Piece. It’s a show we both enjoyed, but have no particular desire to spend a lot of time with after the first three episodes.

- [PAID ONLY] On my personal Patreon, we’re revisiting the Godfather movies and podcasting about them! Listen to our discussion of the first film right here.

- On TikTok, I discussed the recent New Yorker article about Hasan Minaj’s fabrications. I’ll probably write a more detailed piece about it soon based on the numbers this video is doing. Turns out people have strong feelings about comedy!

@davechenskyI’m so #disappointed in #hasanminhaj. #hasanminhajkingsjester #comedy #dailyshow

Tiktok failed to load.

Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser