TIFF 2025 Dispatch #1: Dwayne Johnson Gets Serious, Chris Evans Gets Silly, Russell Crowe Splits the Difference, and a Tale of Two Hamlets

Stephen David Miller gives an update from the Toronto Film Festival, with thoughts on Hamnet, Hamlet, The Smashing Machine, Nuremberg, and Sacrifice

Hello again, Decoding Everything readers! I’m writing to you from an AirBnB in Canada, where I’ve just finished my fourth day (and 15th film) at the Toronto International Film Festival.

In my previous coverage out of TIFF and Cannes, I’ve tried to blend movie reviews with details about the broader festival experience. But this year, my personal and professional life has conspired to make this an even more jam-packed week than usual: When I’m not actively watching movies, I’m either on a call, eating, or sleeping. So rather than try to describe the feeling of being in Toronto, I’ll simply point you to that scene in A Clockwork Orange with Malcolm McDowell’s eyes and ask you to imagine a Tim Hortons in the background. It’s pretty damn close!

And with that, let’s dive in with my first five reviews out of this year’s festival. After this, I’ll plan to share one more dispatch summing up the rest of this year’s highlights.

Sacrifice (Romain Gavras)

One of the joys of attending a film festival is being able to form my own opinions before groupthink gets a chance to set in. So as a rule, I tend to avoid social media while I'm in the thick of it. The only thing I know about online TIFF discourse this year came courtesy of a text from my wife, regarding a Q&A where Chris Evans was asked if playing a failed movie star had "hit too close to home.” A body blow if ever there was one!

I didn't attend the Q&A, but I did catch the movie they were Q-ing about, and I can assure you that Evans was in on the joke. Not that I’d fault anyone on the outside for missing the subtext; read the synopsis of Sacrifice and you still will have no clue what it’s about. When I saw that Romain Gavras had directed a darkly funny ensemble piece about climate activism, I was primed for a bleak comedy retaining the style of Athena. Explosive action paired with a damning critique, funny only to the extent that it’s excessive. But the DNA of Gavras’ previous outing is nowhere to be found here, nor is that of prestige class satires like Triangle of Sadness. If anything, its closest relative is Tropic Thunder. Chris Evans plays a mix between Ben Stiller and Robert Downey Jr: a big budget action star with delusions of wisdom and a desire to make something meaningful. The meta-commentary is unmistakable, and Evans is more than happy to make himself the butt of the joke. We begin with a skewering of faux activism and celebrity, as the Hollywood and tech elite gather in Italy for a decadent gala raising funds for…um…the environment? Whatever satire there is disintegrates into chaos faster than you can say “Anya Taylor-Joy.” From the moment she appears as the leader of a gang of feral, volcano-worshipping children, all real-world parallels go out the window. There will be no incisive social commentary, no dead horse beating about Instagram and hashtags. Instead, we are treated to convoluted lore, multiple dream sequences, a bizarre incest subplot, and John Malkovich sporting a Scandinavian accent.

This is a wild ride, and I can't say it adds up to anything especially insightful. It's messy, broad, and maybe 10 minutes shy from being a train wreck. But I’ll be damned if I wasn’t grinning ear to ear. There’s always enough variety to keep you on your toes, and Evans and Joy do an admirable job at holding the audience's attention. Their gymnastics, paired with Gavras' total commitment to the bit, won me over in the end. Would I feel nearly as high on this absent the late night festival setting? Will I even remember it after I’ve gotten a good night of sleep? The jury’s still out.

Nuremberg (James Vanderbilt)

It feels odd to pivot from a quirky comedy to a historical drama about the Holocaust. But to watch Nuremberg is to repeatedly experience that same tonal whiplash. After all, there are quite a few genres being packed into this fictionalized account of the prosecution of the Nazi high command. It’s a zippy procedural, a clear-eyed memorial, a meaty character study, and a (surprisingly) comedic exploration of narcissism. In one scene we might be chuckling at the self-seriousness of Rudolf Hess; in the next, we’ll be watching real life archival footage of the concentration camps he oversaw. From the inclusion of character actors like John Slattery to the choice of Jojo Rabbit’s Tom Eagles as editor, it’s clear that this tension between heavy and light is intentional. As director James Vanderbilt put it in his post-screening Q&A, he wanted to provoke thought but he also wanted to entertain.

By those criteria, this film is at least halfway successful. Considering its somber subject matter and roughly 2.5 hour runtime, it’s shocking how smoothly Nuremberg goes down. This is the sort of polished, well-acted, inoffensive drama that critics would call “handsome” and mean mostly as a complement. It’s fare that Oscar voters would have feasted on in the pre-Parasite era and are still likely to toss an acting nom today. Russell Crowe is the clear standout in his portrayal of Hermann Göring, Hitler’s disarmingly charming second in command. He channels a dangerous mixture of pride and self-awareness, able to philosophize about his monstrous reputation with a wit that nearly obscures his total absence of remorse or recognition. Rami Malek is less versatile as psychologist Douglas Kelley—the Clarice to Göring’s Lecter—but he’s sturdy in a role that might have easily turned disastrous. Everyone, for that matter, is doing solid yeomen’s work here, both in front of and behind the camera. My two word review of this film would be “good enough.” Good enough to sustain Crowe’s inevitable awards’ season run. Good enough to justify its existence.

Where the film suffers for me isn’t in its entertainment value, or in the craft that undergirds it. It isn’t even in the tonal whiplash I mentioned above; if anything, that’s the most interesting and daring thing Nuremberg has to offer. My issue is with Vanderbilt’s first goal: his desire to make the material thought provoking. Because personally, I couldn’t find much of anything to chew on by the time the credits rolled. It’s moving and relevant to our current moment, of course, but only to the degree that it faithfully recounts the horrors of the Holocaust. For a story set after the fall of the Third Reich, which portends to grapple with grand questions about justice and man’s capacity for evil, I was surprised by how little it had to say on either subject. Tricky moral dilemmas are lobbed up only to be discarded with an aphorism. Characters go through dark nights of the soul as dictated by the screenplay rather than any motivating principle, and some of their most prickly turns are relegated to a title card. Even the courtroom prosecution scene, clearly reaching for an A Few Good Men climactic moment, feels oddly devoid of content. There’s something awkward about the whole exercise, a desire to mimic the tone of moral grandstanding without standing on anything specific. It may be that the transcript of the Nuremberg trials simply didn’t fit this particular genre template, or that the filmmakers feared anything genuinely damning would alienate the audience. Whether screenwriter or viewer, someone couldn’t get a handle on the truth.

The Smashing Machine (Benny Safdie)

That push and pull between a true story and a narratively interesting one is something I also wrestled with (among other martial arts) while watching The Smashing Machine. Benny Safdie’s solo directorial debut is arguably the buzziest of the festival, fresh off a Silver Lion from Venice and already cementing Dwayne Johnson as the man to beat in this year’s Lead Actor race. The energy of its star-studded premiere was infectious. It also detracted from my viewing experience to a surprising degree.

For those who have avoided the ubiquitous trailer, The Smashing Machine transforms Johnson into MMA heavyweight champion Mark Kerr, and follows the ups and downs of his career, his mental and physical health, and his relationship with Dawn Staples (Emily Blunt) through the late 90s and early 2000s. I know next to nothing about the world of professional fighting, but it’s evident that Safdie is aiming for realism. As with Uncut Gems and basketball players, the cast is filled with former and current fighters—some playing a variation of a legend that preceded them (Ryan Bader as Mark Coleman, Oleksandr Usyk as Igor Vovchanchyn, Yoko Hamamura as Kazuyuki Fujita) and others opting to play themselves. When Safdie came on stage to introduce the film, the mood was unambiguously reverential. The real-life Kerr joined the cast alongside him, while the real-life Staples and Coleman waved from the audience. All were met with thunderous applause.

None of this is a problem in a vacuum; I have no qualms with a biopic’s subjects being consulted during production or honored in post. Previous TIFFs have seen Diana Nyad and Tonya Harding walk the carpet under similar conditions. But I find it difficult to square the hagiography surrounding the screening with the movie that I experienced. Because what I watched was a raw, unflinching, often darkly hilarious character study—an exploration of the brokenness that drives men to pummel each other for money, and the way that greatness (or the desire for greatness) can turn you into a husk of your former self. In that light, Smashing Machine feels very much of a piece with previous Safdie brothers movies: loving depictions of self-destructive people, empathetic in the delusional first person. Whether terrible father, heroin addict, bumbling thief or compulsive gambler, they adopt their subjects’ rose-tinted glasses and follow wherever they lead. Johnson’s Kerr fits their template like a glove: jarringly buoyant even as his world is unraveling. It’s an incredible performance, largely because it asks Johnson to turn a mirror to himself in a way that makes Chris Evan’s Sacrifice jabs seem toothless by comparison. A man who cannot even conceive of losing as an intellectual exercise; an icon whose winning grin and friendly demeanor morph into a prison, so fervent in their telegraphing of perfection that the self they were fashioned to protect all but disappears. A veneered smile, signifying nothing.

Except none of that gels with the movie I was sold. And the filmmaking only gives me more reason to doubt my interpretation. The freneticism that defined Safdie’s previous work is largely restricted to the arena. For much of Kerr’s personal story, this looks and feels more like a straightforward biopic than it does a portrait of destruction, with clearly defined emotional arcs and a conclusion that feels downright triumphant. So what am I to make of this odd artifact, this daring character study in the trappings of a significantly less ambitious story? Is it possible to love a movie for the wrong reason?

Hamlet (Aneil Karia)

I’ve never been much of a Shakespeare guy, which is an embarrassing confession to make in a review of one of two “Hamlet”-related movies. It isn’t that I don’t recognize the Bard’s significance, of course. It’s just that, like Mark Kerr / Dwayne Johnson and losing, it’s something I can only really process on an intellectual level. Sure, I might be impressed by the dexterity of the prose, or the creative ways people choose to adapt it, or the structural elements whose fingerprints can be found in virtually every modern story. But as the poet who first blew my mind in high school English once wrote, “since feeling is first / who pays any attention / to the syntax of things / will never wholly kiss you.” I want to be wholly immersed.

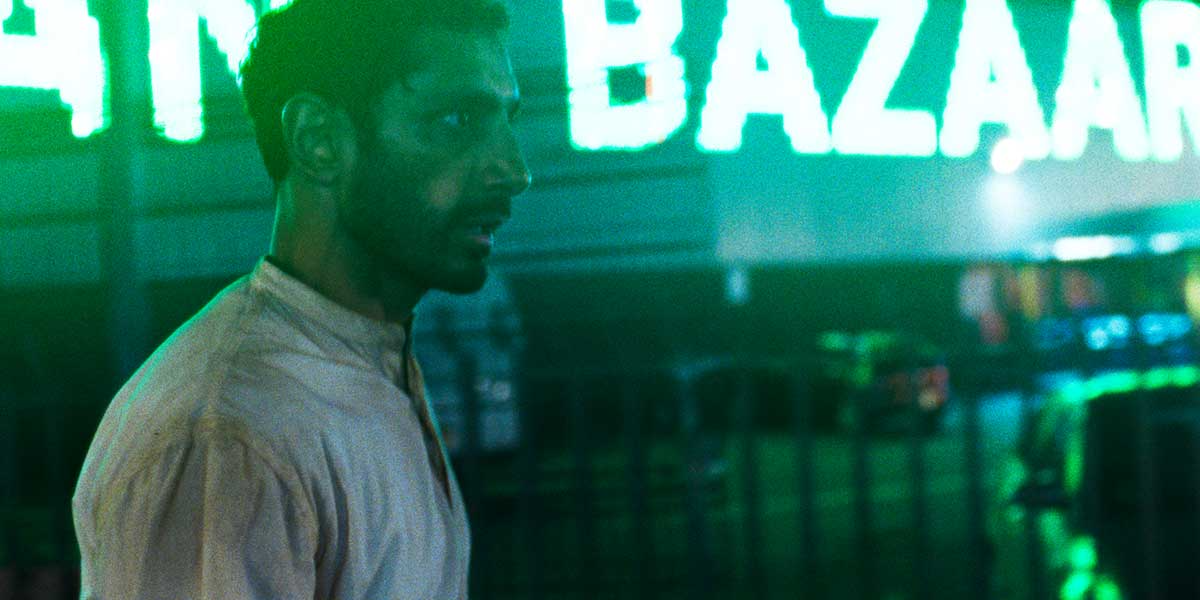

Riz Ahmed discovered Shakespeare around the same age that I discovered Cummings, and fortunately, he did connect on a feeling-first basis. In fact, in his post-screening Q&A he credited his first viewing of “Hamlet” with inspiring him to become an actor. So for well over a decade now, he’s been retooling this passion project. His mission? To communicate the source of his inspiration to a modern filmgoing audience without sacrificing the heart of the original. It’s an ambitious challenge. It’s also one that he, writer Michael Lesslie, and director Aniel Karia have somehow managed to crack.

For the first 20 minutes or so of Hamlet, I’ll admit that I was worried. Although there are some clever tweaks made to fit the story into 21st century London (centering it around a new-money Indian family rather than literal royalty, reworking the Fortinbras storyline to reflect an eat-the-rich class uprising against greedy developers), one aspect remains glaringly unchanged: the prose. Hamlet (Ahmed) speaks in rapid-fire iambic pentameter, deploying spiraling sentences and archaic allusions that would be tough to parse on 0.5x speed with subtitles. Try to keep up and you’ll find yourself drowning (with apologies to Morfydd Clark’s Ophelia). But as I let go of the words and immersed myself in the rhythm, it all clicked into place. With most secondary characters and plotlines stripped away, the specifics take a backseat to the mental state of its protagonist: his rage, his isolation, his fixation on a murder plot that may be real or merely grief-fueled paranoia. Ahmed gives a captivating performance, and Karia clings to it with freewheeling, claustrophobic intensity. Feeling always comes first, most notably in one wordless sequence—their riff on the original’s play-within-a-play—which is so electrifying, I imagine it was the key idea around which the rest of the film was constructed.

As a literal plot, the story remains somewhat out of reach. But as an expression of a particular malaise—the sense that something is deeply wrong with the world, but either to be or not be outraged seems like madness—it couldn’t be more relevant or accessible. I can only hope a wider audience will be willing to take the plunge.

Hamnet (Chloé Zhao)

If Chloé Zhao is attempting to make Shakespeare accessible to a contemporary audience, she certainly isn’t showing her work. Hamnet doesn’t just eschew the updated context of the above adaptation; it eschews context altogether. If not for the synopsis, a viewer could easily spend much of the runtime without knowing this is a fictional account of the famous playwright, his wife, and his children. We are instead simply thrust into a 16th century English countryside, where a rarely-identified-by-name William (Paul Mescal) is listlessly tutoring Latin. During one of his lessons he spots Agnes (Jessie Buckley), from a neighboring family, training a pet falcon in the forest. In an instant, William is bewitched, and Agnes is quick to follow. Their romance feels less like the result of any character machinations than it does some cosmic inevitability, a dormant truth suddenly awoken in their bodies. They meet; they are in love; Agnes is pregnant; they are parents. Their lives together are communicated through a series of fragments.

Hamnet sees Zhao in full Terrence Malick form, and whether that makes you excited or cautious is a good indication of whether this film will be for you. Think hushed dialogue repeated like prayers, half delivered on screen and half in some ethereal, subconscious space; sweeping themes of life and loss, the tragedy (or comedy) of existence; feelings communicated more through cinematography than any dialogue or linear plot. Which isn’t to say this is a departure from the director’s previous work. If anything, it’s the culmination of where she was already headed: the circling camera of The Rider, the reverent hush of Nomadland. Personally, I adore this style of expressionistic filmmaking. And I can’t imagine a cast more suited to the material than Buckley and Mescal, who are perfectly tuned to the register Zhao is operating in—one which isn’t understated so much as emotionally diffuse. Even when it swings for the fences, with agonized shrieks of childbirth or feral howls of grief, there’s a softness that tames its operatic volume. The microphone might clip but we receive it as a whisper, in a universe where even whispers can feel deafening.

Notice that nothing I’ve said so far has anything to do with a Shakespeare play. That’s by design. See, Hamnet takes great care to reveal its emotional crescendos to the audience, and I refuse to spoil any of that with a review. I’ll only say that this film closes with a sequence that stunned me like nothing else this year, and catapulted it to my favorite of the festival so far. Like Riz Ahmed, Zhao aims to communicate the power of Shakespeare’s soliloquies by contextualizing rather than altering his words. But hers feels less like a work of adaptation than it does a borderline spiritual conjuring—a conviction that the mere incantation of certain lines, once we’ve been properly calibrated, has the power to shake us to our core. For as much as I’d loved the film that preceded it, I still entered the final stretch feeling skeptical that any of this would meaningfully connect to “Hamlet,” let alone that “Hamlet” would meaningfully connect with me. I left it, inexplicably, in tears.

Stephen David Miller is the co-host of The Spoiler Warning podcast.