10 Cinematic Pairings That Captured The Mood Of 2024

Stephen David Miller unpacks the year via twenty interconnected films.

Every year, writer/podcaster Stephen David Miller puts together 10 cinematic pairings that defined the year. Last year I was thrilled to be able to share his list with the Decoding Everything audience for the first time and this year I’m pleased to do the same. If you enjoy this piece, check out Stephen’s other writing on this site or listen to his podcast, The Spoiler Warning. -David Chen

Potential Energy

After over a decade of making year-end lists, one thing has become clear to me: Whatever you choose, you’ll eventually disavow it. Neglect your loved ones through the holidays to binge every awards season contender, plumb the depths of your soul to separate “guilty pleasures” from “cinematic achievements,” spend weeks meticulously reconfiguring a Letterboxd-approved ranking, hit Publish, and wait. You might agree with it for a few months, maybe longer if you’re lucky! But at some point you’ll revisit it and wonder what your former self was thinking. Far from being a drawback, the present-tense nature of this exercise is what I most value and want to embrace. We tend to talk about moves as time capsules, but it’s our response to them that crystalizes the moment.

If I could describe this moment in a word, it would be “restless.” Cautious hopes thwarted. Fits and false starts. Potential energy hunting for an outlet. The bone-deep desire to do something, anything, stifled by a world we can’t control. My favorite films of 2024 all spoke to that restless energy in some way: where it stems from, how it feels to hold it, the dangers of misusing it, the dream of an eventual release. In this piece, I’ll be discussing 20 of them, organized as a ranked list of thematic pairings: movies which seem to rhyme with each other, sharing in some fundamental feeling or idea. I hope that by wrestling with them, we can process both the year in cinema and the context in which we received it.

10. Stranded at the Shoreline — ‘Sometimes I Think About Dying’ and ‘Robot Dreams’

It has never felt harder, or more urgent, to form genuine connections. With a steady stream of content pumped directly to our skulls, the pressure differential can seem crushing. We have so much burbling inside, and so few avenues to express it. So we put our best foot forward and hobble towards each other, clumsy human bobbleheads seeking grace.

These are odes to characters who choose to open the release valve, and the awkward bids for connection that ensue. Earnest and satirical, they remind us that love, however clunky, is worth the effort.

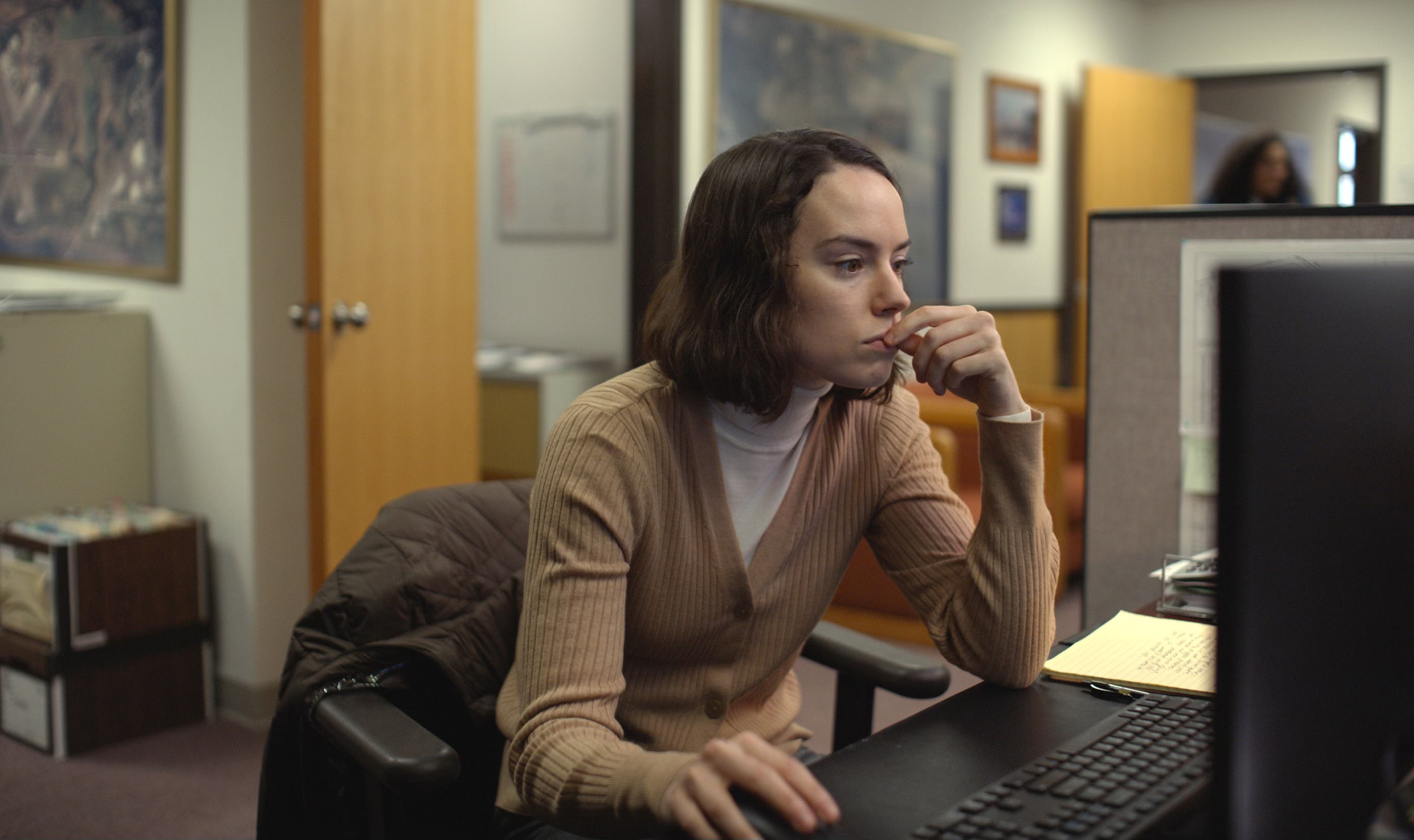

“It’s hard, isn’t it? Being a person?” It’s a sentiment we’ve heard a thousand times before, yet when it’s uttered in Sometimes I Think About Dying, it stings. At this point in Rachel Lambert’s romcom, having spent over an hour inhabiting the mind of Fran (Daisy Ridley), we’ve seen exactly how hard being a person can be. Working a menial office job in a tiny coastal town, Fran is hardly for want of company. She’s surrounded by coworkers day in and day out, and they’d love nothing more than to make her feel included. But whether they’re offering her a slice of cake or a hacky workplace-appropriate joke, Fran’s social anxiety refuses to let her accept it. Instead she retreats into her lonely routine of mild comforts and morbid fixations. All of that changes when Robert (Dave Merheje) joins the team. To an outside observer he may seem blandly pleasant at best, but calibrated to Fran’s wavelength, he’s electric—a wrecking ball of charisma who might chip away at her defenses. Nothing comes easily in the muted romance that ensues, but their attempt warmed my heart more than any slick Glen Powell vehicle.

If Robert thinks he’s in for a challenge, he should talk to the canine protagonist of Robot Dreams. Not that they would respond, of course. Pablo Berger’s animated feature about the blossoming friendship between a dog and a robot doesn’t have a single line of dialogue. What it lacks in words, though, it more than makes up for in expression: This is a charming, sly, and often heartbreaking satire about the difficulty of human(/animal/humanoid) relationships. Be it a feigned shared interest, an overzealous hand squeeze, or a literal chain-link fence, there are countless roadblocks standing in the way of affection. Approach with too much caution and you risk leaving no impression; dive in with head-first fervor and you might find yourself paralyzed, overwhelmed. It’s enough to make you throw up your paws or grippers in despair. But that cocktail of neuroses that sends us tripping over ourselves trying is also what makes it so rewarding. When you finally find your idiosyncrasies reflected in a partner, what used to look like stumbling starts resembling a dance.

Sometimes I Think About Dying is streaming on MUBI. Robot Dreams is streaming on Hulu/Disney+.

9. Seeking a Friend for the End of the World — ‘Flow’ and ‘Gasoline Rainbow’

Our relationships don’t just make life more exciting; they keep us steady. And in a year as tumultuous as this one, I was very much in need of a steadying influence. When the current of history feels overwhelming and there’s nothing left for us to steer, the best we can do is hang on to our companions. Not because they’re anchored to studier ground, but because a shared turbulence is easier to handle. The bigger your footprint, the harder you are to tip over.

These films are about characters drifting through journeys outside of their control. Spun off course and headed toward unknown destinations, they rely on one another to keep afloat.

We return again to a wordless animated story about animals, only this time there’s no society left to skewer. Whatever the world of Flow may once have been is swept away within minutes by a flash flood of biblical proportions. If the audience has little idea what they’re watching, the main character understands it even less. After all, it’s only a cat. Not some anthropomorphized cartoon a la Hello Kitty, mind you; not even a particularly clever cat. Just a skittish little furball who acts about like you’d expect a cat to act in the face of the apocalypse. Gints Zilbalodis’ enigmatic fantasy never offers exposition and we never seem to need it. Instead, we simply float with our feline protagonist through its bizarre new normal, crossing paths with foreboding birds, godlike whales, and one extremely average dog—and we’re transfixed. Despite being set in a universe wholly unlike our own, composed of characters whose thoughts we can’t access, the story transforms into a parable about what it means to be a person. The indelible impact we leave on one another. The short-sighted allure of exploitation, and why it will ultimately backfire. It urges us, without language, to both extend and be worthy of trust. Especially when everything around us is falling apart.

There’s no promise in Gasoline Rainbow that brighter days are forthcoming. If anything, its Gen-Z protagonists assume things will only get worse. The Ross brothers’ hybrid docu-fiction follows a group of high school friends as they take a roadtrip from their sleepy desert hometown to the Oregon coast. How long it will take to get there, or whether they have enough gas or food to make it, are never very pressing concerns. It’s not as if they don’t care about the future, so much as that they’ve accepted how little they can affect it. There’s a shrugging recklessness to their plan, like the ironic nihilism of their humor, which struck me as authentic to this moment. They find community in each other, trading jokes and heart-open confessions as they barrel forward in search of a party they’ve only heard about in passing. It’s aptly called “The End of the World,” and where or when it’ll actually happen is anybody’s guess. However it plays out, they won’t encounter it alone.

Flow is available on VOD. Gasoline Rainbow is streaming on MUBI.

8. Alone in the Wilderness — ‘Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga’ and ‘Good One’

Those tight-knit communities feel particularly vital at a time when larger safety nets are fraying. To live through 2024 was to experience repeated disillusionment: putting faith in leaders, institutions, or an amorphous majority which would ultimately let us down. Times are tough, and there’s no deus ex machina swooping in to ensure a happy ending. There’s just a long road ahead and a mandate to fight.

Two films this year, both coming-of-age stories about young women left to fend for themselves, capture that frustration and the spirit of protest it inspires.

One interesting aspect of Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga is that there’s no doubt as to how it will end. We’ve already seen our heroine burn the system to the ground, and the satisfaction of that can’t be repeated. By giving us a prequel nearly ten years later, George Miller is trying to hone in instead on why she tore it down, the spark that ignited her rebellion. The answer, as Anya Taylor-Joy plays it, is simple. Furiosa pays attention. Wide-eyed and nearly silent, she spends much of the runtime observing the misery around her: the unjust status quo preserved by the stubborn Joe (Lachy Hulme) in power and the chaotic vulgarity of the demagogue Dementus (Chris Hemsworth) who aims to take his place. The Wasteland is merciless, albeit strangely familiar, and what it’s taken from her won’t be restored. Nothing she does will ever balance the scales, a truth Dementus is keen to wield against her. But what is left to do when the damage is irreparable? Slap on a prosthetic clown nose and make a heel turn into cynicism? Shrug and walk away as things get worse? If the idyll of her childhood no longer exists, she can still rally everything she has in its direction.

Good One also functions as a prequel of sorts, though we’re left to infer the saga it sets in motion. Sam (Lily Collias) has her awakening in a different sort of Green Place: a camping trip in the Catskills with her dad and his friend Matt. What’s miraculous about India Donaldson’s indie drama is how miniscule its stakes are relative to the feeling it provokes. Sam’s father (James Le Gros) doesn’t carry a whiff of Dementus’ menace or charisma, and the only thing Matt (Danny McCarthy) shares with Immortan Joe is an inflated sense of self. They’re just a typical pair of middle-aged men, the Platonic combination of “Gen X” and “Divorced.” For much of the runtime we see them exactly as Sam would, out of touch and embarrassing but well-intentioned all the same. What starts as a sharply observed comedy about culture clashes, though, eventually takes on a more emotional hue. Over the course of their hiking trip we see a chasm start to open, between Sam and these men she’s predisposed to respect. Their outdated worldview, a source of eye-rolls in the abstract, has real weight when they’re confronted with a present-tense threat. It’s a heaviness only she seems attuned to, a burden that slows her to a standstill. Why should she carry it alone?

Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga is streaming on Netflix and Max. Good One is available on VOD.

7. The Cost of Caring — ‘Green Border’ and ‘Small Things Like These’

In the face of disillusionment it’s tempting to shut down, quarantining from other people’s pain. Caring is uncomfortable, and who’s to say it would even make a difference? There will always be a reason not to look.

These are stories about people who are living in the margins, suffering while the world averts its gaze. Rooted in recent historical tragedies, they explore the way apathy can camouflage as an accepted social norm, and celebrate the bravery of those who dare to overcome it.

Green Border is not an easy movie to sit through, and that difficulty is what makes it essential. Painstakingly researched and unflinchingly direct, Agnieszka Holland’s drama follows a group of refugees as they attempt to cross from Belarus to Poland. Although the characters are fictional, they’re caught in a very real war waged by Alexander Lukashenko against his EU adversaries. Coaxed by propaganda promising safe transfer into Europe, they’ve fled the violence of their hometowns only to be caught in another vicious cycle: wading through a limbo of swamp and forest, the “Green Border” that separates the countries. If they’re discovered by the Polish police they’ll be violently shuttled back to Belarus, where an equally violent group of guards will repeat the process in reverse. If they encounter a civilian, the deck is similarly stacked against them. Polish law forbids aiding any border-crosser’s passage, and a campaign of dehumanizing rhetoric has stifled the impetus to try. The story’s three points of view each serve a critical function. By showing the true plight of refugee families, it testifies to an urgent humanitarian issue. In the border guards primed to brutalize them, we find a cautionary tale. And from the ragtag band of activists who choose to fight back, we hear a blazing call to action: Don’t look away.

The moral of Small Things Like These is told via Cillian Murphy’s eyes, and at the outset they tend to look downward. Bill Furlong (Murphy), a merchant in 1980s Ireland, has no desire to be a nuisance. A believer in the value of honest labor, he wakes up before dawn to pack heavy sacks of coal which he’ll deliver well until nightfall. He’s a father of five and a good-natured neighbor; if he sees someone hurting, he’ll help them — at least if it’s a solvable need, like offering a pocket full of change to the hungry. Unfortunately, not everything is so easily remedied. Poverty, for instance, the specter of which permeates his town like ash in the air of a mine shaft. Or take the teenage girl living in the local Catholic convent, whose sadness reminds him of his mother. He can’t quite put his finger on it, and it doesn’t seem prudent to dig. Still, that ambient hum that something is wrong persists despite all better judgement. His wife and friends urge him to leave well enough alone, but a louder voice demands he pay attention.

Green Border and Small Things Like These are both available on VOD.

6. Violently Certain — ‘The Seed of the Sacred Fig’ and ‘The Order’

It’s uncomfortable to look directly at things we can’t or don’t want to understand; it’s much easier to fashion a worldview that explains it. The narcotizing allure of easy answers.

These films explore the way dogma can suffocate compassion, contorting complicated realities into simple, rigid shapes. They’re portraits of men who follow their certainties to frightening conclusions.

In Mohammad Rasoulof’s The Seed of the Sacred Fig, the descent into madness is a slow one. Iman (Missah Zareh) is a lawyer who lives in Tehran with his wife and two daughters. Early in the film, he lands a major promotion to serve as a judge for the Revolutionary Court. It’s a welcome change, at first. But when anti-authoritarian demonstrations spring up across Iran, cognitive dissonance starts to chip away at him. After spending his days in court condemning protestors as anarchists and traitors, he comes home to watch the news with his family. There he’ll see images of those same students being brutalized by the police, with a verisimilitude neither Iman nor the audience can ignore: The family drama is a fiction, but this footage is unmistakably real. His daughters are sympathetic to the plight of their peers on screen, for reasons he can surely understand. At the same time, “sympathizer” is synonymous with “dangerous” in his current line of work, and casting judgment on such matters is his duty. As the threat of violence swells around him and the screws continue to tighten, he can no longer reconcile his moral framework with his family. One of them is going to have to break.

What’s disconcerting about The Order is its villain’s total lack of dissonance. Whatever broke inside Bob Mathews, it happened long before we’re introduced. Nicholas Hoult imbues the white supremacist leader with a friendly smile and eerie resolve. Unlike Iman, he has no trouble reconciling his life as a sensitive husband or doting father with the bloodshed he’s ushering in. He’s convinced that his revolution is holy and inevitable, and everything from Jude Law’s stare to Justin Kurzel’s direction carries that same fatalistic streak. Mathews is dangerous not because he’s particularly charismatic or sharp or strategic—his most rousing speech is vague and borderline monosyllabic, explaining that victory, in fact, is better than defeat. The problem is his certainty, and proximity to other men desperate for an answer. He and his small handful of believers form a hermetically sealed bubble, one where hate can smolder till there’s nothing left to question. Police dismiss them as a fringe group so as to minimize the threat, but Agent Husk (Law) has seen this kind of thing before. When smoke starts pluming from an unventilated room, you don’t waltz in with a hose and try to fix it. You clear the house and brace for an explosion.

The Seed of the Sacred Fig has been screening in select theaters across the country, and is expected to come to VOD this February. The Order is available on VOD.

5. To Feel Too Much or Nothing — ‘A Real Pain’ and ‘Red Rooms’

We need a steady flow of oxygen to keep our tether to the world. But with unprecedented access to other people’s stories, it can be hard to breathe without hyperventilating. Absorb too much of someone else’s pain, and you risk becoming a tourist or an addict. Keep it at a distance and you’re likely to grow numb.

These films interrogate our response to the suffering of others. Some characters internalize too much, while others seem to wall themselves off entirely. Is there a correct amount to feel?

Nothing captured that push and pull quite like A Real Pain. Jesse Eisenberg’s understated drama follows two cousins on a “Holocaust tour” in Poland, and if that phrase strikes you as ill-fitting, you aren’t alone. Both men want to connect with their late grandmother and the trauma she endured, but every attempt they make to access it feels wrong. To Benji (Kieran Culkin), the very premise of an educational tour is flawed. When confronted with an atrocity of unimaginable scale, the answer isn’t to learn about it but to scream. But we can’t go through life in a constant shriek, and as David (Eisenberg) is quick to remind him, there are other people within earshot. Benji ought to do what David or I are prone to do instead: muffle that noise until it cools into anxiety, a longer-lived but slightly smoother ache. David wants to take the edge off, while to Benji, the edge is the point. What I love about this movie is its lack of clear-cut lessons. Benji is charming in theory but a stick of dynamite in practice, and while David’s buttoned-up repression can be an easy source of humor, his coping strategy does let him function in the world. Rather than ask us to pick sides, Eisenberg is grappling with two valid, warring impulses, both of which are crucial to survive.

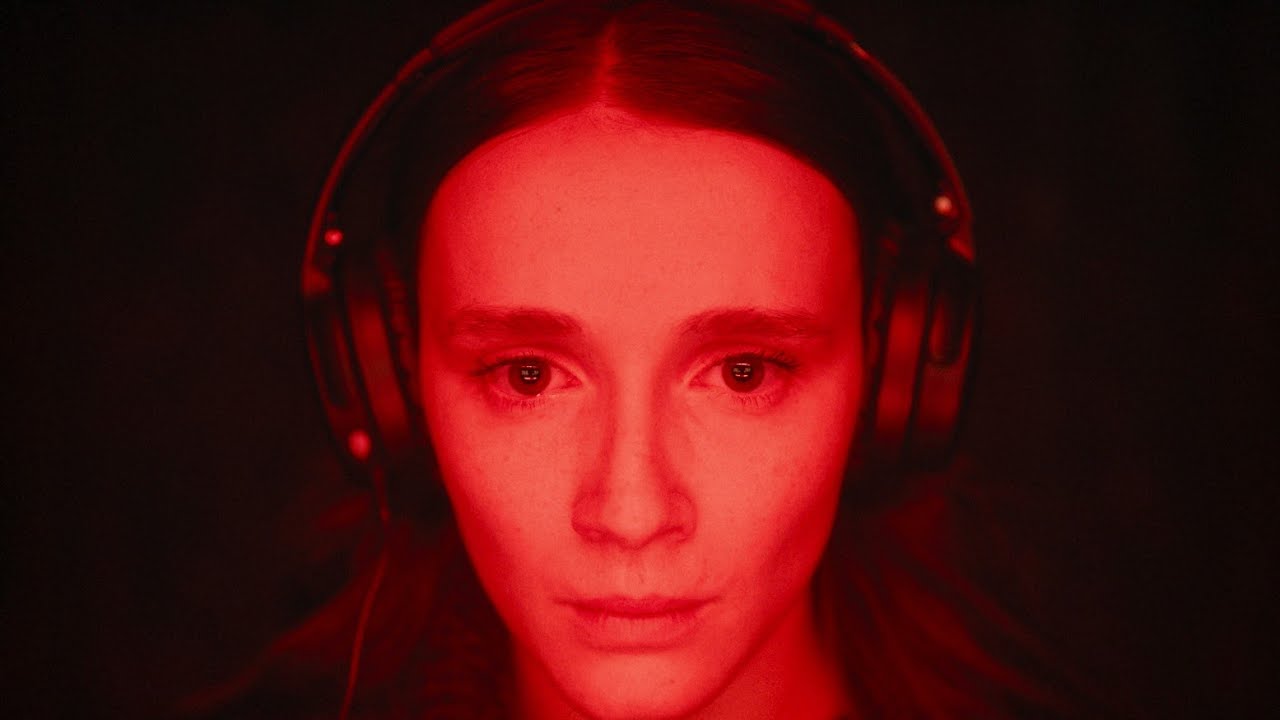

If A Real Pain is a tightly scripted therapy session, Red Rooms is a nightmare that doesn’t end. There is no cathartic release in Pascal Plante’s psychological thriller, and if anyone is grappling with anything they never tip their hand. We open in a Montreal courthouse to adjudicate a high profile serial killer’s case. The camera glides through the opening remarks as if looking for a foothold, moving in slow, unbroken arcs which always settle on a face. At first it’s that of the inscrutable defendant, Ludovic Chevalier (Maxwell McCabe-Lokos), who anchors our focus with voyeuristic intensity. But in time we settle on the film’s true subject, Kelly-Anne (Juliette Gariépy), a fashion model who is staring intently at Chevalier with something. Is it disgust? Obsession? Morbid curiosity? Whatever it is, she’s totally locked in and will remain so for the duration of the film. Like the videos of the killer’s crimes which have become a currency on the dark web, the media frenzy surrounding the trial betrays a wider moral rot. Take the whiff of fetishism in the public’s veneration of his victims. Or the ease with which pundits toss out lurid details as points in a debate. Even the way spectators like Kelly-Anne, or us, seek to comprehend the “why” behind the unspeakable—is that really to an edifying end? Maybe some things are better kept a mystery.

A Real Pain and Red Rooms are both available on VOD.

4. Chemical Smiles — ‘The Substance’ and ‘The People’s Joker’

Our media-obsessed culture is a two way street, turning us all into consumers and performers. With a digital megaphone glued to our hands and a constant imperative to share, it can be hard to separate our genuine selves from the avatars we fashion. The compulsion to conform is enough to drive you crazy.

These movies are about the danger of performative “correctness,” with an emphasis on gendered expectation. They’re depictions of women who strain to fit into an ideal demanded by society, and what happens when their painted-on perfection starts to crack.

There is nothing subtle or nuanced about The Substance, and god bless it for that. Within a few minutes of Coralie Fargeat’s demented body horror, a fuse has been lit and we’re steeling ourselves for the blast. Elisabeth Sparkle (Demi Moore) is a star whose luster has faded. The once beloved actress turned aerobic instructor is nearing her 50th birthday, and with it the death of her showbiz career. So when a voice on the phone offers her an elixir of youth, she accepts it without hesitation. To any audience familiar with fables, it’s obvious that something’s going to give. This isn’t our first Faustian rodeo. The joy of this film comes from knowing exactly what’s coming and still feeling shocked by its crescendos, the sheer magnitude with which it unravels. Although the premise is a cookie-cutter cautionary tale, the experience of watching it is closer to wish fulfillment. Fargeat’s in-your-face direction communicates it, as does Moore’s fearless portrayal—the best in a year with no shortage of stunners about women confined by the culture. Hers speaks to the fantasy of revealing the unpolished self inside, of spewing out the whole bloody mess.

“Pretty girls should always SMILE!” Those words belched by Elisabeth’s sleazy producer also haunt The People’s Joker, though their meaning, like the latter film’s anarchic tone, will shapeshift over time. At the start of Vera Drew’s queer superhero parody, it’s the prescription given by Dr. Crane to her closeted childhood self: Blot out that pesky dysphoric sensation with a puff of Smylex! When she’s training in improv at the prestigious UCB (the United Clown Bureau, of course), it describes the mandate to “Yes, and” her scene partners’ degradations. Even when she’s finally accepted as a trans woman, it’s that sentiment that guilts her into submission. She should be grateful to be validated! She has no idea how good she has it! Harping about trauma is self-involved and petty, and pretty girls should always, always smile. But we’ve seen this story before as surely as Faust’s, IP disputes notwithstanding. There’s an energy stirring inside Vera/Joker the Harlequin, beneath layers of clown makeup and ironic conceit. Freed from its prison, it sparkles.

The Substance and The People’s Joker are both streaming on MUBI.

3. Shine a Light — ‘All We Imagine as Light’ and ‘Anora’

Deep down, we all crave to see and be seen. Regardless of the opaque structures we’re placed in or the homogenizing pall of the culture, there’s a light inside that always finds an egress.

These are stories about that light. They celebrate women who insist upon their value in a society that would rather look the other way, and the radicalism inherent to that act.

On the surface, All We Imagine as Light probably doesn’t seem particularly radical. It certainly isn’t loud, at any rate: Payal Kapadia’s portrait of life in Mumbai is a hushed, unhurried, delicate reflection. But tune in to its rhythms and you’ll find a stirring meditation on repression and resilience. It’s beating in the heart of its three interconnected stories: Prabha (Kani Kusruti) the nurse caught in a long-distance marriage who yearns for a flesh-and-blood connection; her younger roommate Anu (Divya Prabha), whose quiet rebellions run the gamut from dating without parental approval to handing out free birth control; Parvaty (Chhaya Kadam) the cook and her struggle to keep a developer from demolishing her home. We see it too in the faces Kapadia captures in her vérité detours through the night, a resolve that seems impervious to circumstance. Prabha can’t bring her husband back, Anu can’t change her parents, and it’s doubtful Parvaty’s protests can stop Mumbai’s gentrifying sprawl. Still, they do what they can to square the circle with the tools they have in their possession: some as hazy and fantastical as an imagined conversation, others as solid and specific as a rock.

That seamless blend of fantasy and realism is something I also love about Sean Baker’s Anora. Though in this case, there’s no need to mine it for subtle rhythms; you couldn’t ignore Ani (Mikey Madison) if you tried. An erotic dancer and occasional escort, Ani makes her living commanding your attention. From Drew Daniels’ camera to her lovestruck client Vanya (Mark Eydelshteyn), everybody bends towards her presence. But while we marvel at the charisma of her well-honed stage persona, that isn’t what the film is honing in on. Her charm, which sends us floating through the fairytale romance of the first act, is just the prelude to a deeper source of light. We see it in her outrage at being relegated to the supporting cast of someone else’s story, in her tenacity to fight long after the viewer has given up. When our patience is fried and Ani still won’t stop screaming. When she’s shed the sheen of “likability” and demands love just the same. Through the trappings of slapstick that make us laugh at her predicament and the gut punch that hushes the room, it burns bright. The audacity of repeating “I exist.”

All We Imagine As Light is not yet available online. Anora is available on VOD.

2. Sweat, Love, and Concrete — ‘Challengers’ and ‘The Brutalist’

That thrumming “I exist” inside demands an outlet. However hopeless things appear, the human spirit always seems compelled to make a mark. So we channel our zeal and our abilities, whatever we can muster, and we do our best to etch them into stone.

These are stories about that insatiable drive to do something. Taking us from love triangles and rectangular courts to towers of concrete and steel, they’re odes to the shape and scale of passionate endeavor.

When I first saw Challengers, I was in a rut. Stress, burnout, and medical setbacks had left me feeling like an athlete relegated to the bench, a tightly-coiled spectator to my story. Who knew all I needed was a parable about polycules and tennis? Luca Guadagnino’s film wound up being everything its trailer had made me wary of: over-the-top, obvious, unrelenting. And those qualities added up to the most energizing theatrical experience of the year. Every component of this movie, from the thumping Reznor/Ross compositions to the sweat on Patrick (Josh O’Connor)’s brow, from the heavy-handed metaphor to the kinetic camerawork on the court, is boldly, earnestly committed. It isn’t afraid to feel or say exactly what it means. Which isn’t to imply that energy alone was enough to win me over. There are three ingredients at play here, like the corners of our triangle. Intensity, mechanics, and intention. Patrick, Art (Mike Faist), and Tashi (Zendaya). The muscular work being served up is dazzling, but it only lands because of the craft in its execution and Justin Kuritzkes’ razor-sharp script. Working in tandem, they had the effect of a friend grabbing me by the shoulders and shaking. I left the match with its score still pulsing in my skull, wide awake and brimming with conviction.

The Brutalist is another example of form following function. Its protagonist, László Tóth (Adrien Brody), is a man of uncompromising resolve. A Hungarian architect of the Brutalist persuasion, he has a skill for building large, unvarnished, geometrically striking structures, and he’ll pursue that goal despite all rhyme or reason. Brady Corbet must be driven by a similar conviction: One can only imagine how prospective investors tried to dissuade him from making this behemoth. But he and László forged ahead, resulting in a towering statement about creativity, capitalism, and the broken promise at the heart of the American Dream. László insists that it’s the destination, not the journey, that matters in the end. But I think the truth is more complicated. At any rate, the film he’s in belies that explanation. What enthralls me isn’t the skyscraper he toils over, which we only catch in glimpses. Nor is it the ending of his story, which hardly ties a tidy narrative bow. It isn’t even the process of creation—the “journey” in his parlance—though the talent on display is quite impressive. The thing I find myself in awe of is the will to create, the energy that demands one take the journey. It’s the steely determination in László’s eyes after hitting yet another setback; the force that compels a director on a budget to shoot an unmarketable epic about buildings; the thing that makes Tashi leap from her seat with a thunderous, visceral “COME ON.” Winning or losing may well be irrelevant, but your investment in the stakes makes all the difference.

Challengers is streaming on Prime Video. The Brutalist is currently playing in theaters.

1. Someone Else’s Eyes — ‘Nickel Boys’ and ‘I Saw the TV Glow’

Lose that illogical conviction, the fire inside, and you lose your sense of self. Whatever it is that makes you you, it’s essential that you feed it. The alternative is numbness or derealization, the sense of watching life pass by in the third person.

These films ruminate on the pain of losing yourself, and the trauma that can incite it. Rallying cries for empathy and indictments of dehumanizing systems, they also hint at the hope of reassertion.

RaMell Ross’s Nickel Boys is a rare combination: It’s both the most formally stunning work of 2024, and the one I found most personally moving. Often these qualities can feel at odds with each other, with precise control sanitizing intimate expression, the head superseding the heart. What unifies them, here, is perspective. Adapted from Colson Whitehead’s Pulitzer Prize winning novel, the film follows two Black teenagers in Jim Crow era Florida who are sent to the Nickel Academy. The abusive reform school is a fictionalized recreation of the Dozier School For Boys, whose ugliest details have been transposed without embellishment. Shooting almost entirely in a first-person point of view, Ross and DP Jomo Fray reconcile a tension found in a handful of these pairings: neither gawking at real trauma nor turning a blind eye to it, their film embodies it, exploring what it does within a person. What suffering can strip away at, displacing self from self. This is most evident in a scene when Elwood (Ethan Herisse) falls prey to an act of violence. We join him in the first person as he walks into a room, turns to face the wall, then loses sight. Rather than depict the abuse he endures, we are simply left to hear it as photos of Nickel/Dozier students flash across the screen. Then we cut to the perspective of the now-adult protagonist, who has been staring at these photos alongside us. Only here, the camera is no longer behind his eyes; it’s become a spectator, affixed to the back of his head. Why we’re now on the outside, and when that splitting first occurs, are some of the many brilliant details I won’t spoil. But it’s a theme we’ll see repeated throughout the boys’ story. Be it a scene from an old Sidney Portier film or Apollo mission footage, they express through outward projection things the inside cannot hold.

“Do you ever feel like you’re narrating your own life, watching it play in front of you like an episode of television?” It’s a question that looms over I Saw The TV Glow, Jane Schoenbrun’s piercing chronicle of identity and discontent. When Matty (Jack Haven) poses it to Owen (Justice Smith), he declines to answer. Looking inward has never been his preference. “I know there’s nothing in there, but I’m still too nervous to open myself up and check.” In fact, the teenager only really seems at ease when he’s glued to the TV. Specifically when he’s watching The Pink Opaque, the Buffy-coded fantasy he would devour every week. There was just something about it that filled him, a richness the world he lives in hasn’t offered. From his childhood memories which barely exist to the lungfuls that still leave him wheezing, it all seems insufficient, paper thin. But in the glow of a screen, he feels the tug of something more. A pointed allegory for gender dysphoria which also speaks to our broader isolation, Schoenbrun’s film feels like its own pocket universe, fragile and immersive. There’s something about it that gnaws at you, flittering between chilliness and warmth, horror and aspiration, like the pitch shifting vocals of its opening tune or the buzz of Alex Sommer’s Nickel Boys score. The distinct mood it captures is seared into my brain as the most vivid impression of the year. And in its gasping final image, I hear an anthem. It says: Embrace that nameless, restless stuff that’s swelling up within you; fling open the gates and let it breathe.

Nickel Boys is currently playing in theaters. I Saw The TV Glow is streaming on Max.