‘Weapons’ Is a Haunting, Hilarious Fairy Tale for Our Waking Nightmare

The adults are not all right.

This review contains MAJOR SPOILERS for Weapons. Reader beware.

Since 2020, guns have become the leading cause of death among children in the U.S., surpassing car accidents. If a society can be judged by the welfare of its children, then the United States is a failed nation. For all the hand-wringing, “Won’t somebody think of the children?!” we have in the media when it comes to the existence of trans people or drag shows, when it comes to matters that actually affect children’s health and safety, adults are asleep at the wheel. The kids have noticed and are now forced to become their own advocates, abandoned by the people who are supposed to protect them.

In his brilliant new movie Weapons, writer-director Zach Cregger takes this modern horror and places it within a fairy tale framework, utilizing the animating ideas of witches and encroaching evils to highlight how we reached a moment where every adult is only moderately present after tragedy strikes. No one is coming to save the kids, and so, forced to absorb the traumatic present, they must confront evil head-on, becoming soldiers in a battle they never should have to fight in the first place.

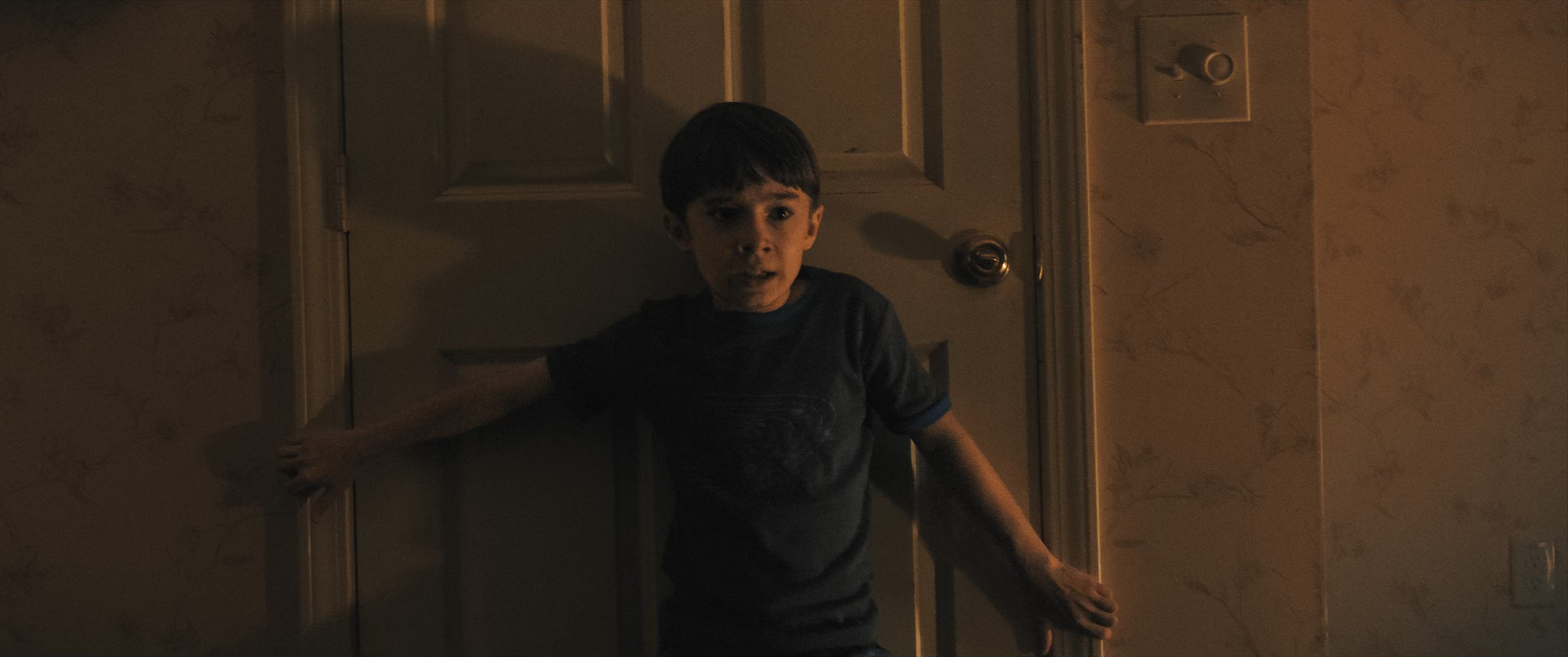

As you’ve likely seen on the posters or trailers, Weapons starts from a simple and unnerving premise: all the kids from a single third-grade classroom got up at 2:17 am, did a Naruto run straight out of their homes, and into the darkness. The children haven’t been seen since, and no one understands what happened. Suspicion follows the children’s teacher, Justine Gandy (Julia Garner), but she’s as hapless as everyone else. The only other member of the class remaining is Alex Lilly (Cary Christopher), but the authorities and community see him as a traumatized child, so they choose to bother him no further.

From here, Cregger cleverly weaves his narrative across seven perspective characters, slightly progressing the overall story to help us understand what happened to the kids and why. The marketing has largely elided the central figure in the disappearances, so please stop reading if you’d like to remain surprised.

The main threat comes into view a little over halfway into Weapons: Alex’s Aunt Gladys (Amy Madigan). Gladys is a witch, and she uses her powers to control others. If she has a person’s hair, she can make them a target. If she possesses an object of theirs, she can make them her puppet. Taking control of Alex’s parents and threatening them if he doesn’t obey, she forces the young boy to take objects from his fellow students. Once she had control of them, she moved them into the house’s basement, where she will presumably use them for future witchcraft that strengthens her lifeforce.

This fairy tale structure is set against a modern malaise where every adult shows why they can’t be counted on to help, even if they ostensibly want to find and protect the children. Every adult who serves as a perspective character is deeply flawed in some way. They’re not monsters—that role belongs to Gladys—but neither are their good intentions enough to protect the community. Justine is an alcoholic. Archer (Josh Brolin), a father to one of the missing kids, is raising a little bully. Paul (Alden Ehrenreich) is an abusive cop who’s cheating on his wife with Justine. James (Austin Abrams) is a drug addict stealing what he can for his next fix. Marcus (Benedict Wong), the school’s principal, seems more concerned with the involvement of CPS than he is with finding the lost students.

Tellingly, Cregger does not concern himself with character arcs for these adults. They help us unfold the story, but their disparate natures also inform us that none of them has the full picture. There’s far too much anger and recrimination with the mysterious disappearances for a community that still has to go about their lives. Archer can paint the word “witch” on the side of Justine’s car, but it’s a childish expression of his misplaced anger. Without resorting to flashbacks, Cregger can show us the fractures in this community that only widened in the face of trauma, and how that allows a figure like Gladys to slither in. More damning is how she’s able to easily function in the open. You don’t need Pennywise from IT hiding out in the sewers; people will overlook the monster staring them in the face as they hunt for answers.

Cregger makes this fairly overt in one dream sequence where Archer, chasing his son to find where he’s gone, looks up in the sky and sees a gigantic assault rifle with the time of “2:17” emblazoned on the side of the gun. Narratively, this leads Archer to later comment to Justine that the kids have been “weaponized,” and that their movements (the Naturo run) are like a heat-seeking missile. Archer understands the short-term answer, but misses how the kids are now locked into a trauma from an external villain. The adults are left rewriting obvious ills as they struggle to understand a larger evil.

The horror tropes here are deeply unnerving, but rarely does Cregger need to rely on jump scares. At times, he even seems to be using our expectations of the horror genre against us, as in one scene where Justine wanders outside her house to see who’s harassing her and leaves her front door open. The implication is that someone will come inside her house for a new scare, but Cregger is playing a longer game, and more importantly, he wants to show us how disconnected the adults really are. He relies on long tracking shots behind the characters’ heads, following them but not letting us see their faces. It helps put the viewer in the mind of a child, looking at an adult but struggling to understand their motivations.

As he showed with his previous film, Barbarian, Cregger knows how to marry the unnervingly horrific with the painfully funny, and his knack for comedy is able to keep the film from becoming a grating, self-satisfied polemic. After Archer has his horrific dream and glimpses the clownish face of Gladys, he wakes up and shouts to no one, “What the fuck?!” While some horror today seems to relish how far it can oppress the audience, Cregger knows when the let the audience breathe and how a well-timed laugh can be like coming up for air before we’re dragged under again by the dramatic tension.

This blend of horror and comedy reaches a perfect apotheosis at the film’s climax when Alex, who provides perspective for the film’s final chapter, turns the tables on Gladys and sends his classmates after the witch. This is keeping with the film’s fairy tale framing, where adults do not come to a child’s rescue. Justine and Archer are left to fight a zombified Paul and James before a mind-controlled Archer tries to choke Justine to death. In fairy tales, the children save themselves, tossing the witch into the cauldron she set for them, or, in this case, ripping her limb from limb. It’s a moment of cinematic ecstasy as we watch these kids retaliate against their monster, crashing through houses and windows, and destroying the monster that sought to destroy them.

It’s a scene designed to thrill and elate, but Cregger doesn’t let us off the hook. After the monster is destroyed, what’s left? Alex’s parents are too traumatized to raise him, and are put in an institution while he goes to live with a nice aunt. He’s safe, but his family has been destroyed, and he can no longer live in the community. Archer carries his son away from Gladys’ bloody corpse, but the voice of our child narrator tells us that not everything immediately went back to normal. “After a year, some of the kids even started to speak again,” is what we’re told as Archer’s son looks into the camera.

The children are becoming weapons because they’re the only ones left to fight evil. In the aftermath of the Parkland shooting, some said they felt inspired by how survivors were speaking out and calling for gun control. Columbine author Dave Cullen wrote a follow-up book speaking to how these kids were trying to change the endless horror of gun violence. I was impressed by the Parkland kids, but also felt deeply ashamed we had reached this point. I was in high school during the Columbine massacre (Cregger is only a few years older than me, so he would have been in high school as well or just starting college). We’ve gone a generation with this kind of horror becoming normalized to where we ask these kids to follow school shooting drills rather than curbing gun ownership in any way. We’re not the monsters wielding the guns, but we are the film’s self-centered adults who have let the monsters come to the door.

The failure of adults to make a better world for kids extends past gun violence and into climate change. You can see it in the Sunrise Movement or the actions of Greta Thunberg. You can see it in adults who pass flailing age-verification laws that don’t work while also supporting AI technology that threatens child privacy and safety. The community is too fractured to see the obvious threats, and when tragedy strikes, they look for scapegoats rather than addressing the failures they’ve manifested. The kids can be weapons for themselves, as we see at the film’s end, but that’s only one outcome. They can just as easily be weaponized for bad actors who masquerade as one of the family.

Even if the kids fight for themselves, Weapons doesn’t see that as a win. It sees that as a societal failure. Cregger wonders how much trauma we’re willing to inflict on the young rather than protecting them as adults should. The film is a stunning work of masterful horror, but the ending in particular is an insightful look at how we celebrate kids for fighting back and then look away at the surrounding trauma. Kids aren’t being traumatized by books about gay penguins. They’re being traumatized by school shooter drills.

But the adults don’t notice. Archer’s face is away from the camera as he holds his son. Archer has what he wants. He’s been restored. His child is not so fortunate.

Weapons is now playing in theaters. Matt Goldberg is a film critic who lives and works in Atlanta. If you enjoyed this review, check out his newsletter, Commentary Track.

Stuff David Chen Has Made

- I’ve spent the past few weeks getting back in the habit of making short-form videos online. You can follow me on YouTube, Instagram, or Tiktok to watch the latest from me. In the meantime, here’s my vlog about watching the new horror film Together, which I thought was great.

- Over on Decoding TV, I reviewed Untamed with Sarah Marrs. We both liked the show, which has a unique setting for a police procedural.

- On The Filmcast, we reviewed The Naked Gun, a movie which we all had a blast with.

- [PAID ONLY] On my personal Patreon, I’m trying out a new show format where I present 5 significant Tiktoks/videos from the week and we react to them. Listen to me trial this out here.