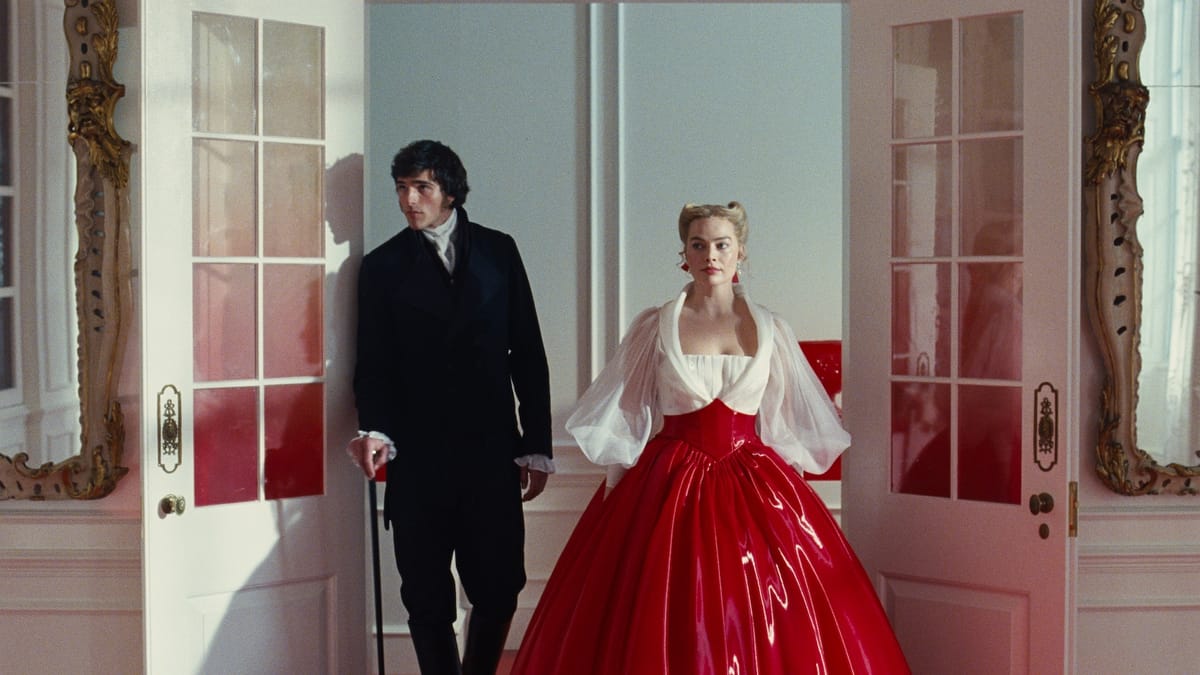

"Wuthering Heights": Emerald Fennell’s Maximalist Adaptation Yields the Story’s Least Interesting Version

By bringing every emotion straight to the surface, the new movie leaves little worth considering.

There’s always room for a new film adaptation of Wuthering Heights. As early as 1920, Emily Brontë’s novel made its way to the screen, and different directors across various cultures brought fresh interpretations to the story. Furthermore, adaptation is always a matter of trade-offs. Fidelity is not the highest value, but omissions and additions should provide some worthwhile element in the movie. Not everything fits into a two-hour film, but readers and non-readers alike should benefit from the changes. Unfortunately, for Emerald Fennell’s new adaptation, "Wuthering Heights" (purposefully styled with quotation marks, which are also doing some heavy lifting given the departures from the book), the writer-director decides to bring every simmering emotion and angst straight to the forefront, relishing the tableaus she can create by highlighting a tortured love affair. And yet the supposed edginess of these images only serves to show how little content they have, eluding the strongest ideas of the novel in favor of flat interpretations. It’s a movie that’s “naughty” in the same way MTV used to be “naughty”: overtly sexual in a way condoned and encouraged by mainstream powers because there’s no real threat beneath the prurient imagery.

Cathy Earnshaw (Margot Robbie) grew up with Heathcliff (Jacob Elordi) after her father (Martin Clunes) drunkenly adopted the street urchin while out at the pub one night. She sees him as her “pet,” even naming him “Heathcliff,” but as they mature, they clearly harbor deep romantic affection for each other. However, their dire financial circumstances cause Cathy to look afield at their wealthy new neighbors, Edgar (Shazad Latif) and Isabella (Alison Oliver) Linton. When Cathy chooses to marry Edgar for the comfort of his wealth, Heathcliff flees only to return as a wealthy gentleman and still in pursuit of Cathy’s affection.

Those who have read Wuthering Heights know it’s not a love story in the traditional sense. It is more a tale of selfishness and generational trauma, where triumph comes in breaking the cycle rather than the constant woe of giving in to your desires. Yes, there is plenty of passion and longing between Catherine and Heathcliff, but they’re also genuinely awful people who, like the tempestuous title, dwell in the harshness of their emotions, causing their drama to spiral outward and ruin those around them. They’re not aspirational, but a cautionary tale paid off in the book’s second volume, which few film adaptations bring to the screen.

Fennell separates her version from others by taking the torment and angst and making it textual through the aggressive visuals. There isn’t a single idea here worth interrogating because the movie is far too eager to announce every thought it presents. It wants you to know that in this telling, sex and death are intertwined. It wants you to know that these characters are captive to their desires. Granted, that’s a far cry from the simmering tension of earlier adaptations, but it also feels tedious once you put it at the forefront. Fennell is following her characters in their quest for immediate gratification, but the plot is based on yearning, so she’s at cross-purposes with Brontë’s narrative no matter how many breaks she makes from the source material. The only way to make it “work” is to distill it down into standard romance tropes, which then loses most of what’s unique about Wuthering Heights.

One of the book’s most striking aspects is how unapologetic it is with its characters. Everyone is deeply flawed, and the power of the writing comes from how Brontë makes us sit with them and unpack their motives. Fennell’s telling quickly softens any sharp edges by defanging its leads. Cathy is selfish and fickle, but her immaturity plays as comical and borderline endearing. Heathcliff, one of literature’s great villains, has no interiority here despite Elordi’s smoldering performance. He is merely the manifestation of Cathy’s immediate desires. He’s a protector when she’s a child, a sex object when they’re adults, and a picture of wealth after she’s married Edgar. The negative qualities get heaped onto Cathy’s childhood friend/servant Nellie (Hong Chau), who takes them on not because she has a perspective or represents any larger ideal, but so that we stay invested in Cathy and Heathcliff’s romance.

This underlying investment, which removes anything too morally objectionable, demonstrates that for all the film’s supposed horniness, it’s as safe and staid as a cup of tea. Once every idea is at the surface, there’s no invitation to delve deeper or have a conflicted feeling. This kind of shallow entertainment worked slightly better in Fennell’s Saltburn because there was at least the value of the unexpected in watching the plot unfold. In "Wuthering Heights," it feels like Fennell has made the easiest, most commercially appealing version that demands nothing of its audience but to sit back and be titillated. That’s not inherently wrong, but it’s a wam-bam-thank-you-ma’am approach that leaves the viewer unfulfilled.

In interviews, Fennell says this is the version of Wuthering Heights that leapt out at her when she was a teenager. “I can’t adapt the book as it is, but I can approximate the way it made me feel,” per a piece on the film in The Guardian. But these feelings play as broad and indifferent towards the material. They're more like what filtered down from Brontë’s book over the decades into romance novels. I don’t fault Fennell for not following the book to the letter, but rather for not pushing herself to find something fresh beyond the visuals. There are even glimmers of a richer adaptation in Oliver’s performance as Isabella, who feels like the only character who grows and changes in interesting ways over the course of the movie. But at its core, Fennell’s "Wuthering Heights" is as handsomely made and as thematically thin as an expensive TV commercial or music video. Her greatest love is not for the characters or Brontë’s storytelling, but for some bombastic art direction and costume design. The characters of the book, as terrible as they are, deserve better.

"Wuthering Heights" opens in theaters on February 13th.