‘Heretic’ Shows the Horror of Being Trapped in a Reply-Guy’s Basement

Scott Beck and Bryan Woods’ new movie nods towards faith but is more concerned with misogyny.

Today I’m pleased to share Matt Goldberg’s review of Heretic. If you enjoy it, be sure to check out his newsletter, .

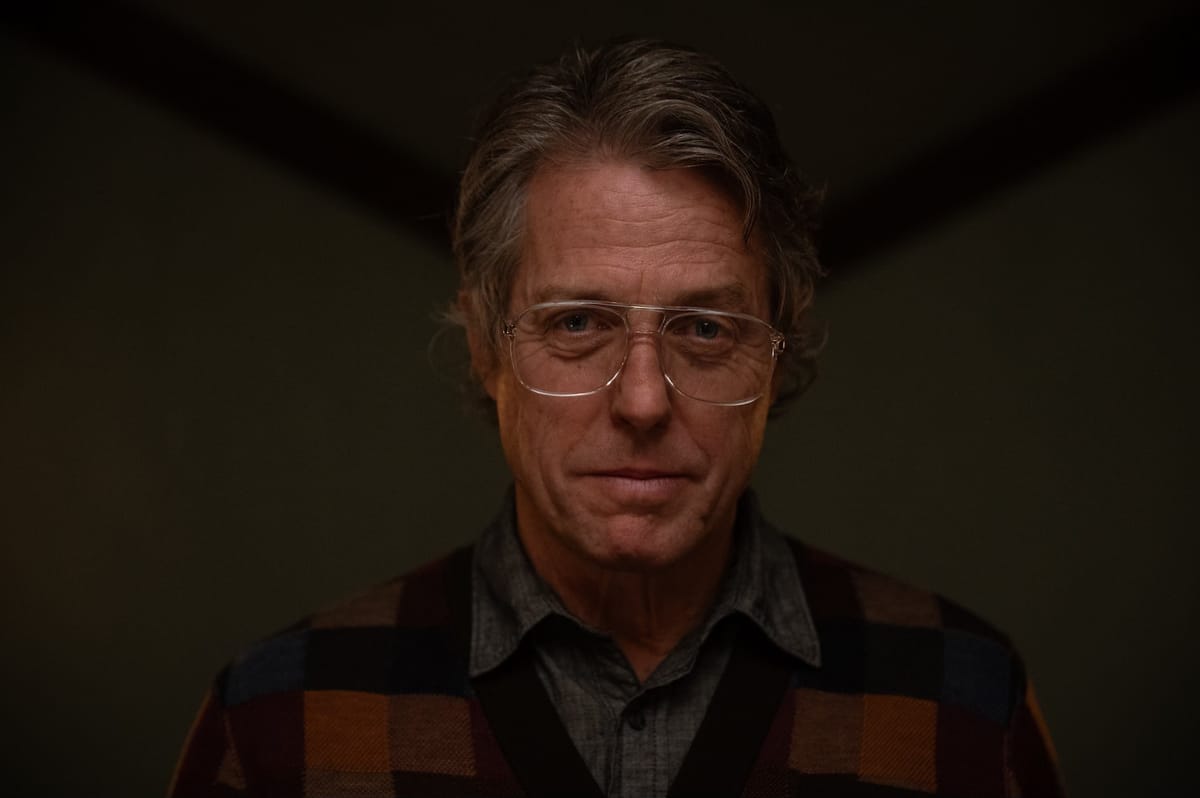

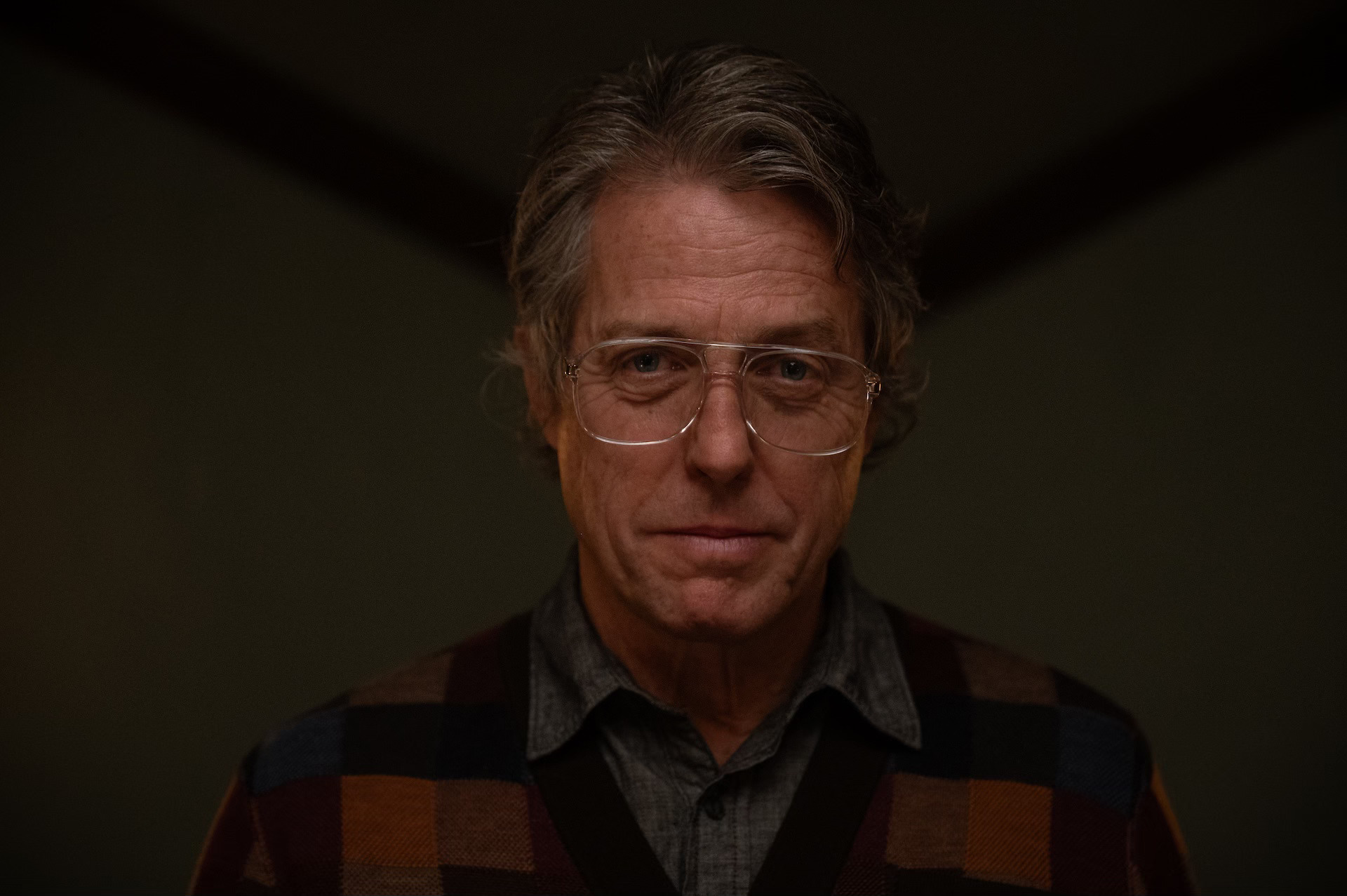

Never underestimate the lengths a guy will go to in order to prove a point. That’s the underlying thesis of Scott Beck and Bryan Woods’ new horror film, Heretic. On its surface, the story seems to be concerned with faith and why we believe what we believe. But it doesn’t take long to discover that the film’s true motives—channeled through Hugh Grant giving one of the best performances of his career—are about how men try to force their worldview on young women, not as a genuine expression of ideas, but as a way to show intellectual dominance no matter how thin and watery the underlying intellect may be.

The film follows Sister Barnes (Sophie Thatcher) and Sister Paxton (Chloe East), two missionaries for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints working in Boulder, Colorado. As a snowstorm starts to swirl around them, they come to the house of the seemingly genteel Mr. Reed (Grant), who appears eager to discuss their faith with them. However, Barnes and Paxton begin to see Mr. Reed playing at something far different than wanting to hear missionaries speak about their faith. Rather than Barnes and Paxton proselytizing to Reed, he’s proselytizing to them through increasingly unhinged parables, comparisons, and demonstrations. Unable to leave the house, Barnes and Paxton must play through Reed’s twisted game if they hope to survive.

Last month, we got Anna Kendrick’s terrific drama Woman of the Hour, which focused on the looming threat of sexual violence that surrounds women and the need to manage men’s feelings as a matter of survival. Heretic operates on a similar level, not in that Reed presents as sexually threatening to Barnes and Paxton (although the movie never ignores the dynamic of this older man looming over these two young men), but rather he presents the need to dominate them through his intellect. Both movies are about how men crave and employ power over women, but whereas Woman of the Hour’s serial killer does this through sexual violence, Reed seeks to force the young women into a state of submission through his pedantry.

Because Reed’s weapon is his words, it gives the audience freedom to laugh at the dark comedy unfolding before us. We’re protective of Barnes and Paxton, but the unique scenario, along with Grant’s performance, provides permission to laugh at the absurdity of the character and his desires. The sheer Britishness of Reed’s behavior makes him play like the most polite and humble version of the Saw villain, Jigsaw. He wants to play a game with Barnes and Paxton, but instead of using elaborate traps, he’s going to debate you with anecdotes, notes from Comparative Religion 101, and what he recently found out from a fun fact-of-the-day calendar. In the same way that Arrested Development noted that a British accent can make a fool seem wise, so too do Grant’s mannerisms mask the banality of Reed’s arguments.

Beck and Woods aren’t primarily interested in addressing matters of faith. It’s not a screed for or against Mormonism or any other theology. While Reed may think he’s testing Barnes and Paxton’s faith, the film always makes clear that their priority, once they see the threat Reed presents, is one of survival. The film understands that while for Reed, this may all be a fun game where he holds power, Barnes and Paxton know this is not the time to break out the literature and start using faith as a cudgel like they’re in a God’s Not Dead movie. The test that lies before them is not one about their beliefs but one in negotiating the massive and fragile ego of the man before them.

This approach makes Heretic feel more immediate than a broad examination of faith because we’re surrounded by Mr. Reeds. They have crept forth from every message board and into every social network, and they always make their presence known through their grinning arrogance and self-satisfied autodidacticism. The movie comes right up to the line of making Reed’s behavior too grating to be amusing, but Grant and the filmmakers always allow us to laugh at his antics despite the threat he presents. He is a familiar figure in the 21st century: a dangerous buffoon. Once you strip away his trappings, he is no different than any online troll whose greatest desire is to win the argument because it can make other people feel small.

Heretic allows us to laugh in the face of these pseudo-intellectuals while never completely dismissing the horror they present. Beck and Woods could have made a straight comedy or satire, but they chose horror because once you get past the smile, the soothing manner, and all the markers of civility, you see the brute beneath the surface whose only desire is to dominate those who have less power than he does. As Barnes and Paxton discover, there’s no use debating with a man determined to argue in bad faith. -Matt Goldberg

Stuff David Chen Has Made

- On The Filmcast, we reviewed the latest Tom Hanks/Robert Zemeckis collaboration, Here. I really liked this film but I can understand why many people find it a bit too maudlin.

- I’ve made a few posts reacting to the election. I wrote about why I don’t think people understand the implications of what they’ve done. On my Patreon (paid), I recorded a podcast with @joyofnapping summarizing our thoughts the day afterwards (Listen here). And on my Instagram/Tiktok, I discussed the importance of grieving.

@davechenskyReacting to #election2024. #selfcare

Tiktok failed to load.

Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser